PHILL NIBLOCK

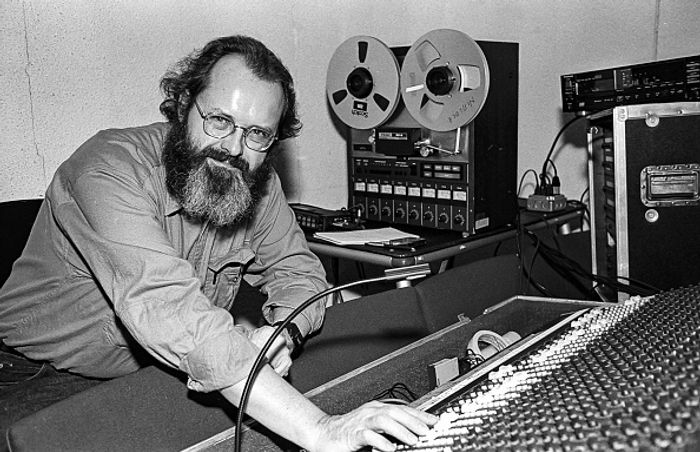

American composer and director of 'Experimental Intermedia,' Phill Niblock @ Phill Niblock Family Archive

Alexander Ivanov

TEXT & RESEARCH

Katherine Liberovskaya

Guy de Bievre

Alexandra Dementieva

ADVISERS & REVIEWERS

Lydiia Griaznova

MANAGING EDITOR, COPY EDITOR

Alexander Ivanov

Alexandra Shcherbina

DESIGN

Paige King

PROOF READER

Alexandra Alexandrova

READER COMPLIER

This page pays tribute to Phill Niblock (October 2, 1933 – January 8, 2024), a trailblazing artist, experimental composer, filmmaker, and photographer. Since 2010, he has been a regular contributor to CYLAND Media Art Lab and CYFEST and has had a priceless influence on how we experience, relate to, and mediate audio cultures. Phill Niblock’s work made us think that sound art goes far beyond contemporary art’s formalized vocabularies and practices towards something more complex and intersubjective. Niblocks’s mastery begins by identifying music as a meeting point between technology, pure physical experience, and artistic solidarity. Although he was strictly a solo artist, the ‘Experimental Elvis’ or ‘Minimalist Madonna,’ as his friend Susan Stenger teased him ①, his vision of the music scene was inclusively pan-generational and community-driven. During the past 40 years, he organized thousands of events at his Chinatown loft under the aegis of the Experimental Intermedia Foundation, and introduced work by a myriad of experimental artists.

This page is a humble attempt to reflect Phill Niblock's work and life through a series of interconnected materials: an essay based on his interviews since 1994, findings from Katherine Liberovskaya’s and CYFEST archives, and a reader. This section also contains playlists curated by artists and composers who knew Phill, offering a subjective, poetic, and institutionally uninformed experience of his music.

***

Phillip Earl Niblock was born in Anderson, Indiana, on October 2, 1933. He was the only child of Herbert Niblock, an engineer, and Thelma (Smith) Niblock, who managed the household. His grandfather provided live music for films, and his father played the piano when he had spare time. In 1956, Niblock earned a bachelor's degree in economics from Indiana University and served two years in the U.S. Army as a lab technician. ② During a stint, he organized his first ‘impromptu concerts’ broadcasting old jazz records on a hospital radio station in Alabama using tape recorders. The army also provided him with the opportunity to see the world. In 1958, he traveled extensively and had a month of leave in Europe. While in Brussels, he had the chance to experience Edgard Varèse's 'Poème électronique.' ③

The same year, after returning to the U.S., he relocated to New York, where he developed a passion for photography and film. He shot jazz luminaries from Roy Eldridge, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach to Duke Ellington and Sun Ra. He filmed the work of choreographers such as Elaine Summers and Lucinda Childs, alongside others affiliated with Judson Dance Theater. ‘I made films that were used in performance or were performance, and the other thing was documenting the work of others.’ — he said in an interview with Natasha Kurchanova in 2015. ④

His photography at the time was developed in response to Edward Weston’s work and was obliged to the Group f/64 aesthetic innovations, which—in an attempt to break with the then-popular Pictorialism—sought to move away from the decoration of reality toward rendering the very fabric of things and the emotional experience of form. ⑤ ‘I was also a Zone System photographer. I did enough photographic work to know what it was and to have a real concept of it.’ he told Kurchanova. ‘In some of my work I shot and developed film to deal specifically with the range of tonalities it offered. Edward Weston was most influential for me in photography because of the controlled way he was shooting and his tendency to make abstractions out of extremely real things.’ ⑥

American composer and director of 'Experimental Intermedia,' Phill Niblock poses for a photograph at the sound-check for a concert of his works in the World Music Institute 'Interpretations' series at Merkin Concert Hall, New York, January 17, 1991. © Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

Phill Niblock did not receive formal musical training. His approach to learning embraced art as a living process, placing utmost importance on participation, listening experiences, and self-education. In 1961, he attended a performance of Morton Feldman’s piece ‘Durations,’ which legitimized a radical perspective on musical composition for him. ‘It was an incredible revelation, that you could have a piece without rhythm and melody, and these long tones. It really was in a way a permission to do music in a similar kind of way. I could work with that idea. Then I was very interested in the microtonal stuff,’ he said in a 2007 interview with Paris Transatlantic Music Magazine. ⑦

Despite achieving success in performance photography and film, he was seeking an opportunity to pursue his creative endeavors. ‘I had an incredible amount of material,’ he remembers. ‘For instance, there was a film of a piece Yoko Ono did, of which I shot just 100 feet. I showed it to her and the guy she was with and they suggested I should dedicate myself to documenting their performances and I would someday be famous. It was an incredibly bald statement, and I simply walked away!’ ⑧

Niblock composed his first pieces in 1968. Called ‘environments,’ they were multiple-image projections of 16 mm films or slides with live dance elements performed by young dancers who had quit working for Cunningham and switched to Judson. The first intermedia performance occurred in December 1968, the last in 1972. The following year, he initiated ‘The Movement of People Working,’ a series of films he would work on until 1992. Non-narrative, unedited long-take videos depict people primarily in rural or coastal areas engaged in various labor activities, such as farming, fishing, or boat repair, in countries spanning from China to Portugal and Puerto Rico to Romania. In this expansive durational project, he utilized cinematic techniques to make ordinary routines seem abstract, choreographic, and temptiщng to witness while altering the relationship between photography and film. ‘I was never really known as an experimental filmmaker because I was really interested in concrete, clear images. I was interested in photographic looking film.’ he told FRIEZE magazine’s Geeta Dayal in 2004. ‘So I started to film people working as sort of dance movement, essentially. So it didn't have to do with what they were doing; it had to do with the way they moved in the frame. Very much dance film, not ethnographic or political in any way.’ ⑨

A collection of videos from the personal archives of Phill Niblock and Katherine Liberovskaya, made during their travels to Sumatra in 1990 (0:00 — 3:00) and Romania in 1991 (3:00 — 5:52). These videos have been graciously provided by Katherine Liberovskaya specifically for this publication. © Phill Niblock & Katherine Liberovskaya

‘The Movement of People Working’ immerses viewers in a contemplative environment, allowing them to tune into the rhythms and repetitions of bodily movements. Infused by the Minimalist desire for formal clarity, rigor, and dematerialization of the object, it simultaneously highlights the boundaries between what is known as ‘minimal’ and ‘figurative.’ ‘The idea was to strip out most of what film is about. To delimit the structure. I think it's easier to say that the music is minimal, rather than the films. It's a little harder to explain how the films are minimal,’ he told Paris Transatlantic. ⑩

Like Niblock’s other films, ‘The Movement of People Working’ was often shown within a collective space of performance or concert. He envisioned a stage with musicians and a temporary community of people carrying different listening experiences as the natural setting for his minimal photography-looking videos. Although the visual and aural parts of Niblock’s performances look perfectly balanced and complementary, he stressed the disjunction between the experiences of listening and looking. When asked about through lines across his work in various mediums, he answered evasively, stating that the main thing for him is the feeling of loss of time that music gives the audience. ‘The music is very much about that, about losing time, having no meter to it. There’s no conceptual link between what’s in the film and what is in the music.’ — he told FRIEZE magazine’s Geeta Dayal. ⑪ For this reason, the video sequence was never planned: the composer traveled with a stack of DVDs and would improvisationally choose which film to show.

Niblock's musical style defies easy description. In interviews, he prefers to evade questions or offer intricate descriptions of the technology behind his work rather than to conform to specific definitions or narratives. He did not adopt the role of a musician. Instead, he preferred the term composer, highlighting that his music doesn’t ‘develop’ or structure as is customary in traditional composition. Indeed, the method he used was far from what is typically thought of as musical development. Since 1968, Niblock has been recording tones produced by an instrument using audio tape, arranging them into multi-layered settings he called 'clouds.' Initially, he would prescribe the microtones by tuning the instrumentalist, asking him or her to play at specific Hertz frequencies. Later, he used ProTools to make the microtones as he composed the pieces. The resulting composition is a stream of dense, superimposed drones rich in microtones and stripped out of rhythm, melody, and typical harmonic progression. ‘So when you combine 57 and the octave above would be one hertz on, you get a lot of very strange combinations. What happens in the middle of the piece is it becomes — at its most complex — virtually pure distortion. It comes apart,’ he explained to the Wire’s Mark Sinker in 1994. ⑫

Phill Niblock, Katherine Liberovskaya, Al Margolis, Mia Zabelka, Winter Convergence, Performance/concert. CYFEST 10: Frame of Reference, 2017. © Anton Khlabov/CYLAND MediaArtLab

Niblock's soundscapes are site-specific, spatially and architecturally responsive. They can be performed with or without musicians, but they can never be re-enacted the same way twice. As Mark Sinker argues, 'everything, from speaker system to volume to where you are in the room, produces too many variables in each piece.’ ⑬ The only constant thing is that the music must always be played very loud.

As Dan Warburton wrote in a review, Phill Niblock’s style combines 'the conceptual rigour of minimalism with the impact and volume of rock.' ⑭ The effect he wanted was a distilled, naked, hard experience, contrasting the orthodoxy of classical music and the ‘conceptual dead-end of post-war serialism and its ferocious complexity.’ ⑮ In his performances, high acoustic pressure causes the sound to condense. The off-scale decibel level creates a new concert experience not reduced to compensatory entertainment, formal expectations, or a desire to conform. An aesthetic decision that comes at the cost of the audience’s comfort activates a highly corporeal type of listening, allowing the whole body to explore and mediate the physical weight of music. ‘Phill had a profoundly unfussy approach to contemporary composition. He flooded rooms with waves of sound, until you could swim in them: music as a kind of geological presence.’ — told musician and sound artist Thomas Anksermit to the Wire in 2024. ⑯

Secondly, using a high volume of up to 115 dB is essential, for it reveals previously hidden characteristics of a sound or instrument. ‘When you turn it up loud enough, the cello disappears completely and you hear only this screaming cloud of high harmonics, whereas at low volumes it just sounds like cellos. That's one of the reasons for playing this music loud that a lot of what happens becomes prominent at high volumes.’ he explains. ⑰ Unsurprisingly, listening to Niblock's soundscapes is, first and foremost, a live here-and-now experience; his music doesn't fully work on the record.

David Watson performs Watson and Niblock, Live music performance. CYFEST 15: Vulnerability, HayArt Centre, Yerevan, Armenia, 2023. © Edith Bunimovich & Anton Khlabov/CYLAND MediaArtLab

Niblock made music from drones and instruments such as cellos, hurdy-gurdies, bagpipes, trombones, and even vacuum cleaners. ⑱ Since 1970, he has been writing pieces for small ensembles and creating scores. In these pieces, the musicians were 'tuned' to pitches they heard through headphones.

Though his work kept pace with technological developments and the types of musical instruments he worked with were highly diverse, he was selective. He preferred working with old instruments, distilling them to their essence rather than buying into marketing or fetishized promises of experimentation for its own sake. ‘I thought about making electronic music in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and I could never stand the sound of electronic instruments. It was the days of FM synthesis, which I didn't really like at all. It never really got that much better as far as I can see. I really liked the sound of traditional instruments, which I continue to work with. When I went back to seriously making new music in the early ‘90s, I went back to making it with those instruments,’ he told FRIEZE. ⑲

David Watson performs Watson and Niblock, Live music performance. CYFEST 15: Vulnerability, HayArt Centre, Yerevan, Armenia, 2023. © Anton Khlabov/CYLAND MediaArtLab

For over 22 years, Niblock has collaborated with his life partner video artist Katherine Liberovskaya on a number of various live, video and installation projects. Among them, performative or fixed poetic visual and aural works assembled from material recorded in the field. For example, Liberovskaya describes their last collaboration, created four months before Niblock's passing. ‘Wind Waves / Rumble Mumble was the last project we completed together with Phill in the summer of 2023 at an informal residency in Lithuania at the country residence of artist friends Francisco Janes and Jurate Jarulyte.’ — she remembers. ‘A single 22-minute long-sequence shot from a fixed point of the different wave patterns the gusts of wind were making on the surface of the water of a pond, as well as the life of the fauna and flora around it, on a very windy day, accompanied by a collage of sounds captured and mixed by Phill Niblock, assisted by Francisco Janes, in the surrounding area. The fixed point of view of the video was from the veranda of the house on a pond of Francisco and Jurate in the Lithuanian countryside where Phill and I spent entire long August days with them and their young daughter Carolina. The soundtrack was derived from audio recorded by Phill during long drives we took along the unpaved gravelly roads through the woods and fields of the environs that Phill and Francisco processed and mixed in Francisco’s studio there. Originally, we were each working on a piece of our own. Phill on a sound piece (Rumble Mumble), me on a video piece (Wind Waves). But when we finished our pieces, we discovered they were the same length! And when we combined them, they fit together so well! Like some of the Cage / Cunningham collaborations... So this video-audio piece was meant to be Wind Waves / Rumble Mumble.’

Wind Waves / Rumble Mumble, 2023. Single-channel video and installation loop, 22:00, color, stereo, HD.

Video: Katherine Liberovskaya. Sound: Phill Niblock, Francisco Janes.

Phill Niblock was a prominent curator who contributed significantly to the New York experimental scene. His work was interwoven with collectively organized music experience and was based on mutual respect and open collaboration. For more than 40 years, he has been the director of the Experimental Intermedia Foundation and curated EI's XI Records label. EI was founded by Elaine Summers in 1968 to provide organizational support for artists working in intermedia forms. While retaining the avant-garde spirit of the place, Niblock transformed it into a social nexus for a generation of cutting-edge yet unrecognized musicians and composers. ‘The idea was to invite people who would have had a hard time getting concerts elsewhere," he comments. "It didn't make any sense to invite people like John Zorn for instance, who was performing all the time and curating. Nor did it make any sense for Cage to perform at El, although he would have done it.’ ⑳ However, the events he curated at EI were not only about 'giving emerging artists a place to be' but also entering a collective experiment territory where juxtapositions of artist and listener, insider and outsider, public and private, music and sound, would melt and transform each other.

In addition to his curatorial practice, Niblock worked with students. From 1971 to 1998, he was a professor at The College of Staten Island, part of the City University of New York, teaching photography, film, and later, video.

Phill Niblock offers a rare definition of minimalism. Rather than celebrating it as an unproblematic entity or a label, he defines it more widely as a performative practice that disrupts the formal determinacy of musical expression and the social patterns of composing, listening, and concert-making. He was one of those who broke the glass ceiling, inspiring a host of younger musicians and composers to follow their path. His life asserted that one's voice is developed through participating in a community and exploring a sense of belonging rather than by adhering to the rules of academic economy. Self-taught with no formal education, he changed the music of the second half of the 20th century. He turned his Center Street loft into an internationally known hub for experimentation, free from any pressure for ‘visibility’ or ‘sustainable development’—something that even the world's leading museums can only dream of.

Phill Niblock, Katherine Liberovskaya, Al Margolis, Mia Zabelka, Winter Convergence, Performance/concert. CYFEST 10: Frame of Reference, 2017. © Anton Khlabov/CYLAND MediaArtLab

‘There was 20 years between us, and Phill instinctively took on multiple roles as surrogate father, advisor, supporter and networker on the one hand, colleague, companion and deepest personal friend on the other.’— told media artist and composer Arnold Dreyblatt to the Wire in January 2024. ‘There was no contradiction in these alternating modes, Phill was never in any way hierarchical, he was there for you on all levels, young or old, famous or not, sharing his international contacts, his humour, telling you who you gotta meet, showing his recently completed film and music works, recounting his recent acquisitions (romantic and technical), all in one breath.’ (21)

After his retirement at the end of the 90s, he toured up to 250 days a year until his final months. ’It's been a great journey, see you on the other side,’ he told his friends on the phone the day before he died. He will be sorely missed.

Phill Niblock, Music and films, Performance. CYFEST 14: Ferment, Composers Union of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia, 2022. © Anton Khlabov/CYLAND MediaArtLab

REFERENCES

1. “He truly loved what he did and he did it until the very end”: tributes to Phill Niblock (January 2024) in The Wire Magazine.

2. Williams, Alex. "Phill Niblock, Dedicated Avant-Gardist of Music and Film, Dies at 90" (2024) in The New York Times.

3. Niblock mentions visiting the Phillips Pavilion in interviews with Natasha Kurchanova and Geeta Dayal. These interviews are cited in the references for this essay. Commissioned for Phillipps Pavilion at the 1958 World's Fair to affect human sensibility via audiovisual means, this eight-minute tape piece featured bells, sirens, electronic signals, human voices, and a piano accompanied with a film of still photographs. The poem was played through hundreds of loudspeakers, blending the music with Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis’ architecture. More information: Licht, Alan (2007). Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli. PP. 35-36.

4. Interview with Phill Niblock by Natasha Kurchanova (2015) in BOMB Magazine.

5. Group f/64 by Lisa Hostetler (2004) in The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

6. Interview with Phill Niblock by Natasha Kurchanova (2015) in BOMB Magazine.

7. Interview with Guy de Bièvre by Bob Gilmore (2007) in Paris Transatlantic Magazine.

8. Khazam, Rahma. Shimmer Me Timbers. Intermedia is the message in Phill Niblock's amplified walls of sound, which have hypnotised musical pacesetters from Cage to Jim 0'Rourke (2001). The Wire Magazine — March 2001 (Issue 205). PP. 31.

9. A Sence of Time. Interview with Phill Niblock by Geeta Dayal (2016) in FRIEZE Magazine.

10. Interview with Guy de Bièvre by Bob Gilmore (2007) in Paris Transatlantic Magazine.

11. A Sence of Time. Interview with Phill Niblock by Geeta Dayal (2016) in FRIEZE Magazine.

12. Din Locator. Interview with Phill Niblock by Mark Sinker (1994) in The Wire Magazine — June 1994 (Issue 124). P. 41.

13. Ibid.

14. No Melody, No Rhythm, No Bullshit. Interview with Phill Niblock by Dan Warburton (2006) in The Wire Magazine — March 2006 (Issue 265). P. 35.

15. Ibid. P. 35.

16. “He truly loved what he did and he did it until the very end”: tributes to Phill Niblock (January 2024) in The Wire Magazine.

17. Khazam, Rahma. Shimmer Me Timbers. Intermedia is the message in Phill Niblock's amplified walls of sound, which have hypnotised musical pacesetters from Cage to Jim 0'Rourke (2001). The Wire Magazine — March 2001 (Issue 205). PP. 31.

18. Phill Niblock. The sound that time forgot: remembering the experimental musician and filmmaker by Geeta Dayal (2024) in 4Columns.

19. A Sence of Time. Interview with Phill Niblock by Geeta Dayal (2016) in FRIEZE Magazine.

20. Khazam, Rahma. Shimmer Me Timbers. Intermedia is the message in Phill Niblock's amplified walls of sound, which have hypnotised musical pacesetters from Cage to Jim 0'Rourke (2001). The Wire Magazine — March 2001 (Issue 205). PP. 32.

21. “He truly loved what he did and he did it until the very end”: tributes to Phill Niblock (January 2024) in The Wire Magazine.

The authors and publishers gratefully acknowledge permission granted to reproduce the copyrighted material. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted material. The publishers apologise for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this publication.

ROOMS FOR THOUGHTS

A playlist for Phill Niblock

Luca Forcucci

The collaboration with Georges Lewis, a prominent figure in contemporary music, indicates the implication and vision of Niblock regarding new forms of music. When played loud enough, his music becomes a personal intimate composition, a physiological response to one’s own ears. The physicality of his sound resonates in a micro(tones)/macro(room) relationship. Such sonic and spatial aspects blend in various forms in the music of Pauline Oliveros, Eliane Radigue, Suzanne Ciani and Maryanne Amacher. Niblock’s work includes, too, an exceptional rich series of films. The first time we met, he showed me his collaborative film with Arthur Russell, Terrace of Unintelligibility. Phill’s musical continuum exists in the music of Julius Eastman’s and Charlemagne Palestine, two musicians present in the early years of his Experimental Intermedia loft. My own piece, Room, reflects the absorption of the above influences.

A FRIEND'S VOICE IN MY HEAD

A playlist for Phill Niblock

Sergei Komarov

Lydiia Griaznova

FURTHER READING

① Phill Niblock: Working Title. Les presses du réel, Dijon, France.

④ Gilmore, Bob. "Phill Niblock: the orchestra pieces." Tempo 66. № 261 (2012): 2-11.

⑥ Komarov S. The Vanitas of Sound Art // Leonardo. 2022. Vol. 55. №. 6. pp. 676-683.

⑦ Saunders, J. (Ed.). (2009). The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music. Routledge.

⑨ Obrist, Hans Ulrich (2013). A Brief History of New Music. Zurich: JRP|Ringier.

⑩ Licht, Alan (2007). Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli.